Parent Peer Advocacy, Mentoring, and Support in Child Protection: A Scoping Review of Programs and Services

Yuval Saar-Heiman1, Jeri L. Damman2, Marina Lalayants3, and Anna Gupta4

1Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel; 2University of Sussex, Brighton, UK; 3Hunter College, New York, USA; 4Royal Holloway University of London, UK

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a5

Received 13 July 2023, Accepted 15 January 2024

Abstract

Objective: Parent peer advocacy, mentoring, and support programs, delivered by parents with lived child protection (CP) experience to parents receiving CP intervention, are increasingly recognized internationally as inclusive practices that promote positive outcomes, but little is known about what shared characteristics exist across these types of programs and what variations may exist in service delivery or impact. This scoping review examines 25 years (1996–2021) of empirical literature on these programs to develop a systematic mapping of existing models and practices as context for program benefits and outcome achievement. Method: Studies were selected using a systematic search process. The final sample comprised 45 publications that addressed research on 24 CP-related parent peer advocacy and support programs. Data analysis explored how programs were studied and conceptualized and examined their impact on parents, professionals, and the CP system. Results: Substantial variation in program settings, target populations, aims, advocate roles, and underlying theoretical frameworks were identified. Across program settings, existing empirical evidence on impact and outcomes also varied, though positive impacts and outcomes were evident across most settings. Conclusions: Findings from this review highlight the need to account better for parent peer advocacy and support program variations in future practice development to ensure alignment with inclusive and participatory principles and goals. Future research is also needed to address current knowledge gaps and shed light on the impact of these differences on individual, case, and system outcomes.

Keywords

Child protection, Parent advocates, Parent mentors, Parent supportCite this article as: Saar-Heiman, Y., Damman, J. L., Lalayants, M., and Gupta, A. (2024). Parent Peer Advocacy, Mentoring, and Support in Child Protection: A Scoping Review of Programs and Services. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 73 - 88. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a5

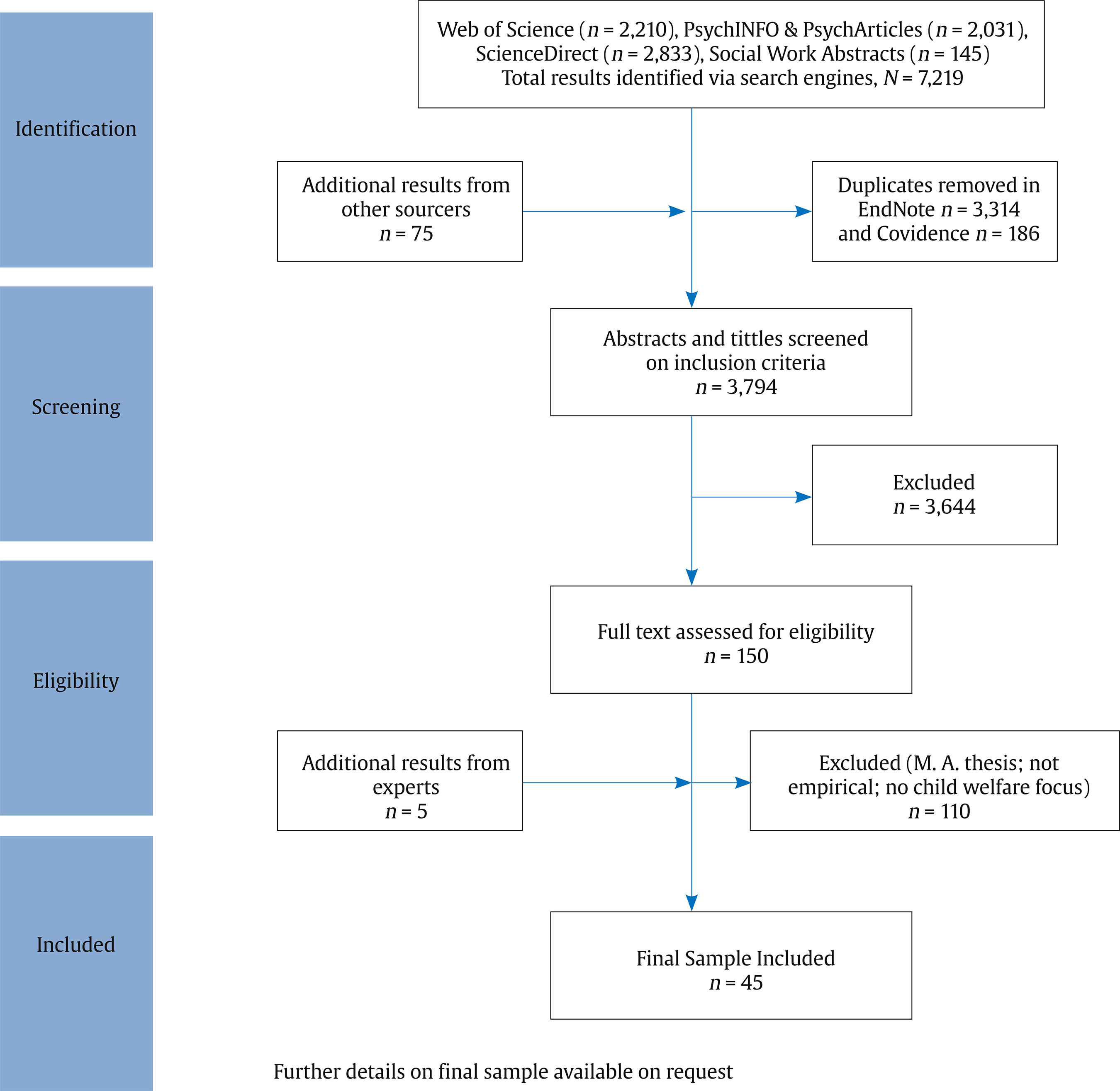

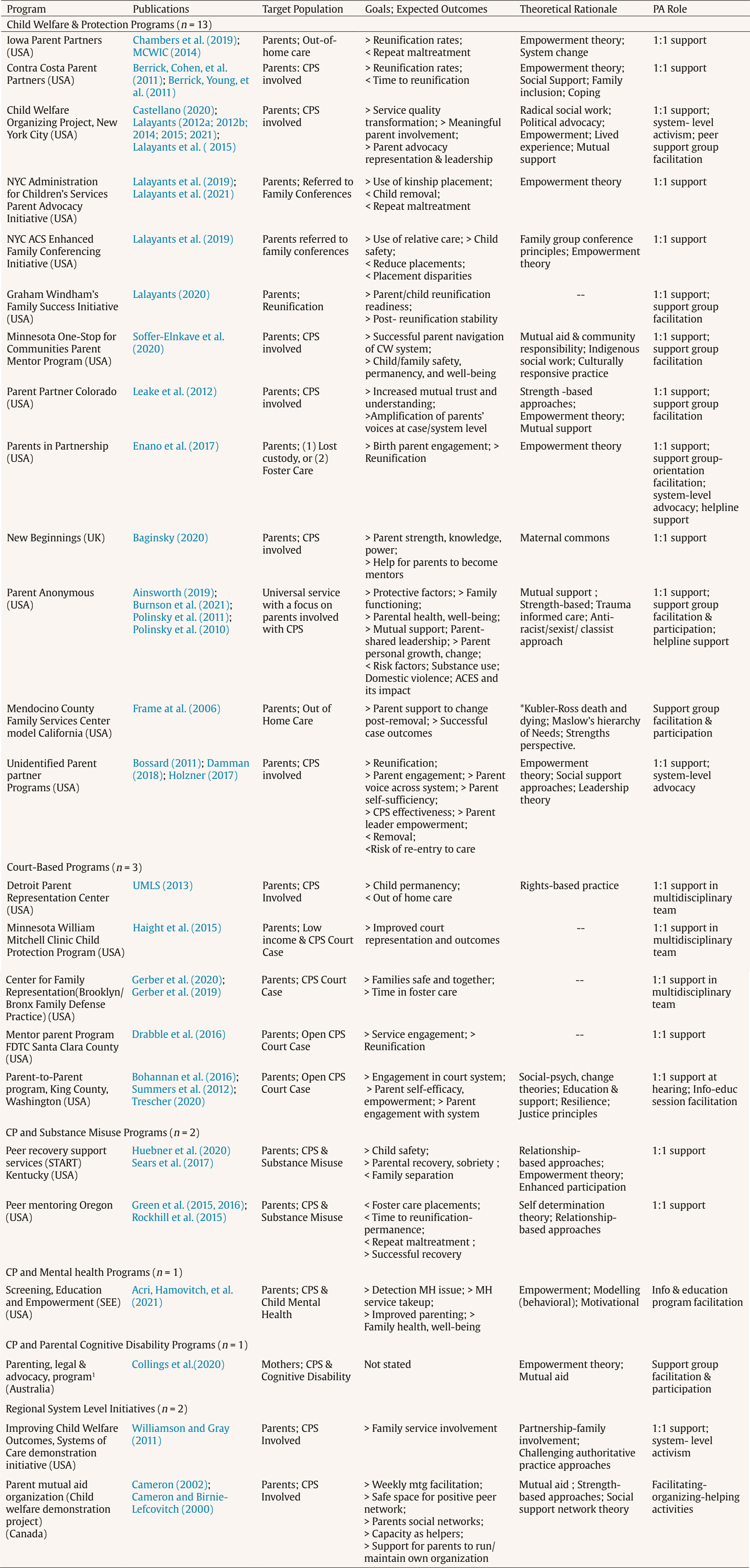

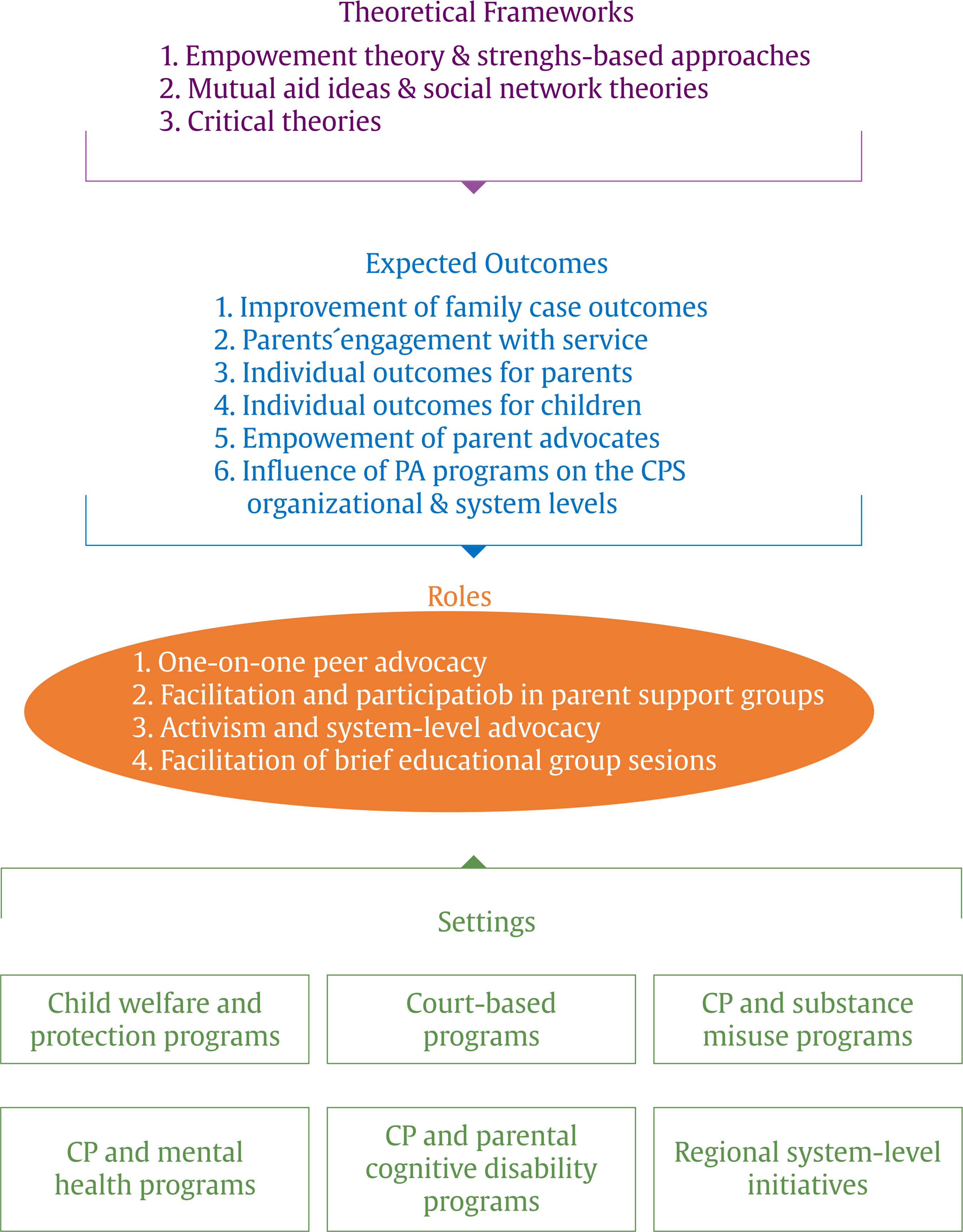

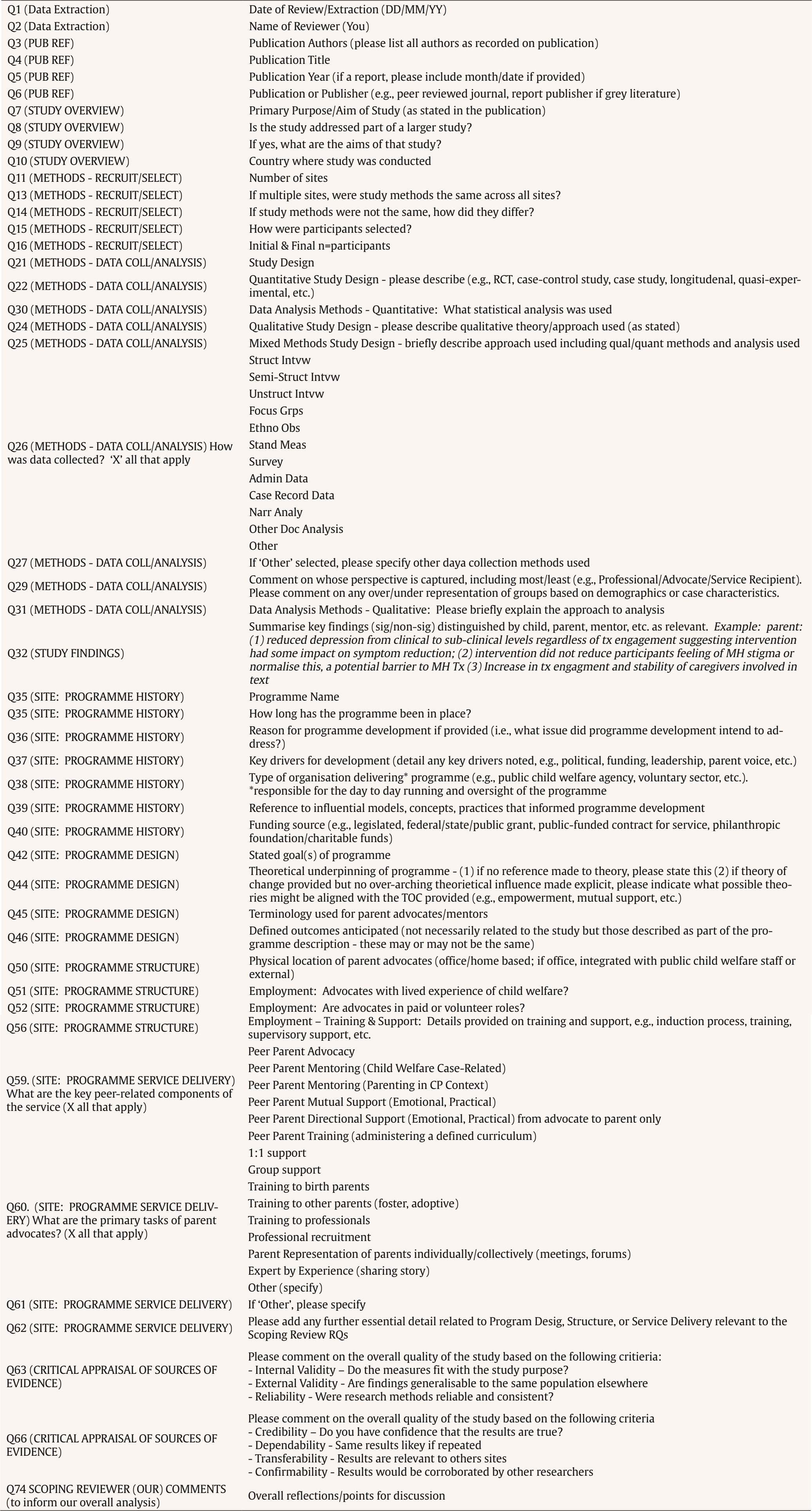

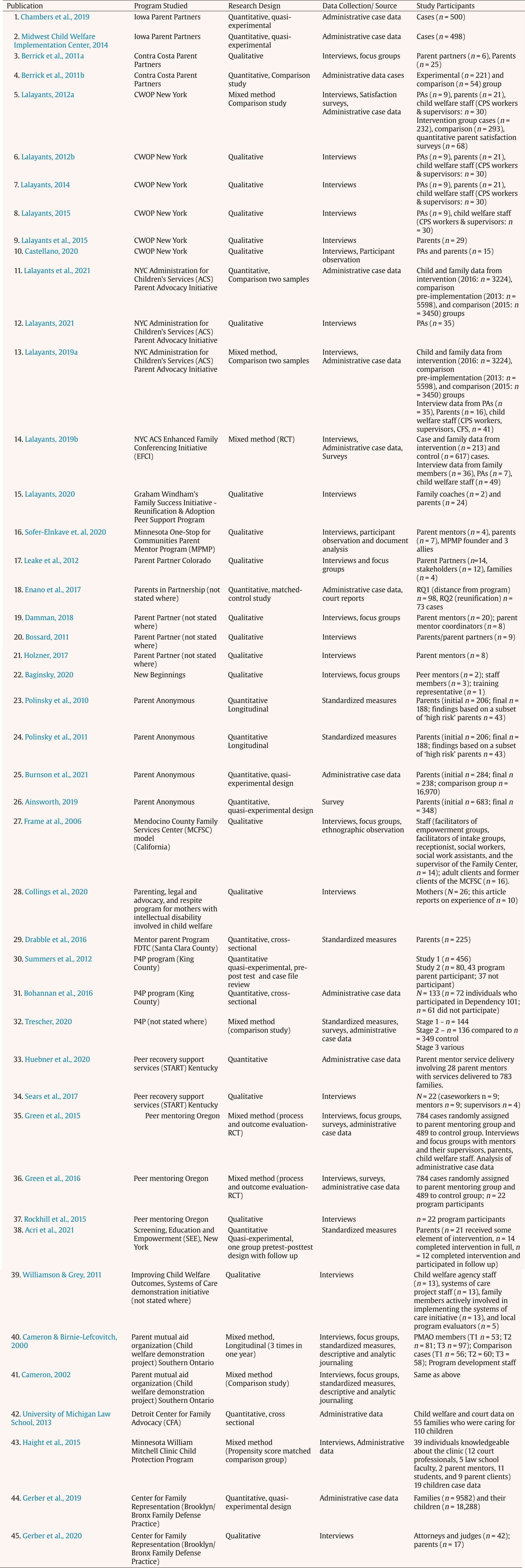

Correspondence: heiman@bgu.ac.il (Y. Saar-Heiman).Child maltreatment has long been recognized as one of the most pernicious social problems in countries around the world. Given its scale and scope, finding effective ways to address child maltreatment is essential from both practical and moral perspectives (Berrick & Altobelli, 2018). The social policies states adopt to protect children from harm and promote their well-being vary greatly, reflecting historical, social, cultural, and political contexts. Responses to child maltreatment in countries in Europe and North America have been broadly conceptualized as being “child protection” or “family service” in orientation, although over time, changes and areas of convergence have been noted (Gilbert, 1997; Gilbert et al., 2011). The United States, the United Kingdom, and other developed anglophone countries, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, tend to have legalistic and adversarial child protection (CP) systems that focus on individualized notions of risk and parental pathology with little attention to social harms (Featherstone et al., 2018; Parton, 2022). During the past several decades, there have been appeals to reform CP systems, particularly in these countries, where it has become increasingly evident that punitive interventions disproportionately impact families living in poverty and communities of color (Bywaters & the Child Welfare Inequalities Team, 2020; Detlaff et al., 2020; Hyslop, 2022; Lonne et al., 2019). Increasing parental engagement has developed in response to these calls for change (Haworth et al., 2023). Although parental engagement with services is considered an essential component of effective and ethical interventions (Gladstone et al., 2014), empirical research points to the difficulty of engaging parents in CP interventions and reveals parents’ negative experiences of them (Gibson, 2019; Merrit, 2021). Indeed, innovative practices that promote meaningful participation to address experiences of unjust and unequal treatment of parents affected by the CP system are receiving increasing attention (Featherstone et al., 2021). Parent peer advocacy, mentoring, and support programs are examples of the inclusive practices gaining international attention, and early evaluations demonstrate positive outcomes. These terms, often used interchangeably, refer to initiatives that involve parents with lived experience of the CP system working to promote the participation and rights of other families involved in the system through individual case-level advocacy within organizations and wider CP policy and practice forums (Tobis et al., 2020). However, little is known about what shared characteristics exist across these programs and what variations may exist in service delivery or impact. This scoping review of 25 years of empirical literature on parent peer advocacy, mentoring, and support programs aims to develop a systematic mapping of existing models and practices as context for program benefits and outcome achievement. Parent Peer Advocacy and Support in Child Protection Despite the broad consensus regarding the ethical and practical importance of promoting parents’ participation, studies have found that the voices, needs, and experiences of families involved in the CP system are often excluded and ignored by both policymakers and child welfare professionals (Corby et al., 1996; Thorpe, 2007). Furthermore, various factors associated with CP involvement, such as prior adverse child welfare experiences (Kerkorian et al., 2006), fear, distrust, and other negative emotions (Healy & Darlington, 2009), power imbalances between families and workers, as well as parental shame and stigma (Scholte et al., 1999), can significantly affect engagement and participation. While engaging parents subject to CP investigations can be challenging, meaningful involvement in decisions, planning, and delivery can positively impact family outcomes (Featherstone & Fraser, 2012). Parent peer advocacy and support programs promote family engagement, inclusion, and participation at the practice and policy levels (Tobis et al., 2020). These peer-delivered programs draw on the shared experiences of parents to offer advocacy and support in individual and group settings. Parent advocates (PA), also known as parent partners, parent mentors, or parent leaders, are parent peers who have personally experienced the child welfare system and now provide peer mentoring, support, and advocacy services to parents who are presently involved in the system (Lalayants, 2014). PAs possess a firsthand understanding of how risk factors can affect families’ lives and parenting abilities and have acquired knowledge on effectively addressing these challenges and navigating the child welfare system (Lalayants, 2012a). Although programs delivered by parents with lived experience have been gaining popularity across various settings, little is known about the nature of peer advocacy and support programs, variations among programs, and how the current evidence base reflects these differences. Furthermore, there has been a lack of attention to the theoretical and ethical frameworks that inform and support this practice (Damman, 2018). Recently, two systematic reviews (Acri, Falek, et al., 2021; Saeteurn et al., 2022) have attempted to synthesize the literature on parent peer programs to assess the effectiveness of PA programs on case outcomes. Other reviews have addressed intersecting topics such as group social support (Pérez-Hernando & Fuentes-Peláez, 2020) or parent advocacy beyond peer-delivered models (Fitt et al., 2023). Acri, Falek, et al. (2021) examined quantitative studies (n = 12) focusing on USA-based peer mentor interventions in child welfare that deliver unidirectional support by parent mentors to parents and other carers (e.g., in foster or kinship care). Studies were not limited to CP service-specific programs or those delivered by parents with lived child welfare experience. Saeteurn et al. (2022) reviewed long-term outcomes of peer parent programs delivered by parents with child welfare lived experience in four quantitative studies that involved an intervention group and a comparison group. Findings from these reviews explored the characteristics of the interventions and generally pointed to favorable outcomes, particularly regarding reunification. The present study expands on prior reviews by examining birth parent peer advocacy and support in CP services specifically and broadening the quantitative, outcome-led focus of prior reviews. It aimed to systematically map the theories and rationales underlying these programs and their models, structures, and practices to shed light on their impact and achievements. The expanded search criteria included non-USA studies, qualitative and quantitative research, and grey literature sources spanning 25 years. This broad approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the range of existing programs and how they have been conceptualized and studied over time. Current Study The present study employs a scoping review with a systematic approach using PRISMA guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018) to enhance reliability and capture a thorough and detailed understanding of the existing literature on various peer advocacy and support programs in CP. The following research questions drove this review: a) how are parent peer advocacy and support programs “studied”?, b) how are parent peer advocacy and support programs “conceptualized” in the empirical literature?, and c) how do parent peer advocacy and support programs impact parents, professionals, and the system? Search Strategy Using our research questions, the first author developed the initial search strategy in consultation with the three other team members and the Royal Holloway University of London social science librarian. The strategy for conducting a comprehensive systematic international literature review involved a multifaceted search using bibliographic databases, grey literature, and expert consultation. Web of Science, PsychINFO, PsychARTICLES, Social Work Abstracts, and ScienceDirect were the databases used. These databases were selected after we conducted a preliminary search of 10 databases and found that these five provided the highest yield of relevant results. Child Welfare Information Gateway, Google Search, and Google Scholar were utilized for the grey literature search. Search terms included the following keywords: child welfare, child protection, children’s services, peer, parent, partner, advocacy, mentoring, and support. Eligibility, Exclusion, and Inclusion Criteria Publications that fulfilled the following criteria were included in the study: 1) reporting empirical research focusing on programs delivered by parents with lived experience of the CP system to parents currently involved with child protective services (CPS); 2) focusing on program development, delivery, or outcomes; 3) published in English; 4) published between January 1996 and December 2021. Our decision to examine research from the last 25 years stemmed from the fact that the first federal initiative that promoted parent advocacy in the US, the Improving Child Welfare Outcomes Through Systems of Care demonstration initiative, was launched in 2003 (Williamson & Gray, 2011). Therefore, we decided to begin our search seven years earlier to ensure we included initiatives developed before the federal initiative. Studies were excluded if they involved parents without lived experience of CPS in service delivery (e.g., foster parents), focused on parent advocacy programs outside of CPS, or were theoretical or conceptual. Search Outcome and Screening Our search yielded 7,219 publications from database searches and 75 publications from other sources noted above. Publications were imported to EndNoteTM (V20) Referencing Management Software, and 3,314 duplicates were eliminated. Results were then moved to Covidence, a specialized screening tool, and 186 duplicates were removed manually. A three-stage screening process followed. First, the first and second authors conducted a title and abstract screen of all results (n = 3,794) for relevance to the inclusion criteria. Next, each of the 150 publications selected from the title and abstract review process underwent a full-text review by at least two authors from the team. When there was a disagreement between the authors regarding a publication’s eligibility (e.g., disagreement on what programs fell within the definition of CPS), the team met to reach a consensus regarding the final sample (n = 40). Last, we contacted individual experts in the field who were sent the list of papers identified for inclusion and asked them to review it for missing studies. Based on their recommendations, we added five publications that met the inclusion criteria. In total, 45 publications that met the inclusion criteria were included. Figure 1 presents a PRISMA flow chart from the initial search results (n = 7,219) to the final sample (n = 45). Data Extraction and Analysis We subjected the final sample of publications to data extraction using a descriptive analytic framework developed by our research team and guided by the research questions. An Excel charting form guided the data extraction from the sample articles. We developed the form a priori, iteratively defining the variables and determining categories to answer our research questions (see Appendix A for the full framework.) The framework included two main categories of variables. The first category addressed the research presented in each publication, e.g., study design, study aims, research method, sample size and characteristics, and main findings. The second category of variables addressed the characteristics and impacts of the program site presented in the publication, e.g., program history, design, structure, service delivery, and the role of peer parents. After data from each publication was extracted and entered into the spreadsheet, each of the authors was assigned a different set of variables (e.g., setting and target population, program aims and expected outcomes, theoretical framework) and analyzed the similarities and differences within the sample in relation to the different domains. Finally, the team met multiple times to discuss the links between the different domains and develop the structure of the findings. Overview of the Study Sources and Designs The sample of 45 publications (for an overview of the sample characteristics, see Appendix B) examined 24 parent advocacy (PA) and support programs. Among the studies examined, 41 were conducted in the USA, two in Canada, one in Australia, and one in the UK. Thirty-two studies were published in academic peer-reviewed journals, followed by evaluation reports (n = 8), PhD dissertations (n = 4), and non-academic journals (n = 1). Of the 45 studies selected, only eight were also represented in one (n = 4; Acri, Falek, et al., 2021) or both (n = 4; Acri, Falek, et al., 2021; Saeteurn et al., 2022) prior systematic reviews noted previously. Research methods employed to investigate the operation of PA programs included qualitative (n = 20), quantitative (n = 16), and mixed methods (n = 9). The primary qualitative methods were semi-structured interviews (n = 29) and focus groups (n = 9). Other methods, including ethnographic observations (e.g., Castellano, 2021) and discourse analysis of program documents, were also observed (e.g., Soffer-Elnekave et al., 2020). Quantitative designs included three randomized controlled trials (RCTs), eight comparison designs, three cross-sectional designs, three longitudinal designs, seven quasi-experimental designs, and one matched-control trial. For the quantitative studies, data sources were collected through administrative case files, standardized measures, and surveys. Studies involving participants approached the issues they addressed from the perspective of parents receiving services (n = 20), parent peer advocates (n = 17), non-peer professional program staff (n = 11), and various stakeholders in the community (n = 6). Programs Characteristics While all 24 programs represented involved parents with lived experience supporting parents currently involved with CPS, we observed significant variation among them regarding setting and target population, aims, the role of parent advocates, and the theoretical frameworks underlying their work (See Table 1: Program Overview). Setting and Target Population We identified seven CP-related settings in which parent peer advocacy and support programs operate. The most prevalent setting was within “child welfare and protection programs” (n = 13). Indeed, most programs targeted families already involved with CPS, aiming to support them in the process of engagement and associated challenges. While some programs were open to any parent involved with CPS (e.g., Burnson, 2021), others focused on parents in specific phases of involvement, such as referral to a family conference (e.g., Lalayants, 2021) or child removal from home (e.g., Frame et al., 2006). The second type of program identified in our review was “court-based programs” (n = 5), where PAs were part of an interdisciplinary team alongside attorneys and social workers, representing parents with CPS involvement, including open dependency or family court cases (e.g., Gerber et al., 2020). In addition, within the judicial context, PA programs supported parents alongside more traditional court systems as part of family or dependency court programs (n = 2). Three additional settings with parent advocates included CP programs that address the intersection of CPS with other family needs and challenges, including “CP and substance misuse programs” (n = 2), “CP and mental health programs” (n = 1), and “CP and parental cognitive disability programs” (n = 1). Last, we identified “regional system-level initiatives” (n = 2), which refer to time-limited, funded efforts to systematically implement collaborative and family-inclusive services and promote natural support networks in specific regions (e.g., Cameron et al., 2000). Program Aims and Expected Outcomes While all the programs aimed to enhance support for parents navigating the often intimidating and confusing process of CPS involvement, there was notable diversity in expected outcomes. We identified six categories of expected outcomes across programs, with most programs encompassing multiple categories. The most prevalent category of expected outcomes related to the “improvement of family case outcomes” (n = 16). These outcomes pertain to the child’s placement, the intervention’s timeframe, and the stability of decisions made during the process. A second category focused on “parents’ engagement with services” (n = 11). These programs anticipate that the intervention will enhance parents’ experiences with services and engagement with professionals. The next two categories centered on “individual outcomes for parents and children”. Regarding children, nine programs anticipated that the intervention would promote various elements of their well-being, for example, by ensuring their safety, preventing the recurrence of maltreatment, and guaranteeing they received optimal services. Similarly, six programs expected outcomes directly related to parents’ well-being. Another aspect that some programs aimed to address was the “empowerment of parent advocates” (n = 6). In these programs, parent advocates’ development, empowerment, and well-being were integral to the intervention. The last and least mentioned category of expected outcomes pertained to the “influence of PA programs on the organizational and system levels of CPS” (n = 4). These programs recognized that involving PAs is not solely about supporting parents but also involves harnessing the power of lived experience and challenging problematic power dynamics within the system. Parent Peer Advocacy and Support Forms, Roles, and Functions In the realm of child welfare we found four primary forms of parent peer advocacy and support. The most prevalent form was “one-on-one peer advocacy” (n = 19), where advocates offered various types of support to parents in managing their cases. In this form, eight key functions were performed by one-on-one peer advocates: 1) assisting parents in their “initial engagement” with services by actively recruiting them and employing their shared experiences to approach parents non-threateningly (Green et al., 2015); 2) providing parents with “emotional support” by fostering informal, non-judgmental, and caring relationships; 3) supplying parents with “essential information” about system requirements, the process they were navigating, and their rights within that process; 4) playing a crucial role in supporting parents in “developing their support networks” by linking them to community services and helping them overcome feelings of isolation and shame; 5) assisting parents in “actualizing their rights” and accessing tangible support by guiding and accompanying them to relevant social institutions and services; 6) empowering parents to “voice their needs and express their position” regarding decisions concerning their families and case plans; 7) playing a vital role in helping parents “implement the agreed-upon case plans” by conducting regular meetings, identifying areas where parents may be struggling, and addressing these difficulties; and 8) serving as “mediators between parents and professionals” to facilitate effective communication (Berrick, Cohen, et al., 2011). Moving on to another form of parent advocacy and support, we found that the “facilitation and participation in parent support groups” were relatively scarce in the realm of CP despite their prevalence in mental health and substance abuse services (Acri, Falek, et al., 2021). Parent support groups operated on the principle that shared experiences could enhance individuals’ understanding of their own circumstances while reducing isolation through the development of a supportive social network. In our sample, PAs facilitated and participated in support groups in seven programs. However, only three of these programs explicitly stated that PAs were co-facilitators, while the role of parents in the other programs remained less defined. The third form of parent advocacy identified in our sample was “activism and system-level advocacy” (n = 5). Several programs also integrated system-level advocacy alongside one-to-one PA. In these programs, PAs had the opportunity to participate in decision-making, contribute to the development of policies, procedures, and practices, and provide training for PAs, foster parents, and CPS workers. Furthermore, we identified two regional initiatives where PAs acted as activists in providing interventions for parents (organizing and running recreational and educational activities and developing formal and informal support networks for parents) that were also intended to empower PAs to become support program leaders (Cameron, & Birnie-Lefcovitch, 2000). The fourth form of parent advocacy involved the “facilitation of brief educational group sessions”. This form was observed in two programs (Acri, Hamovitch, et al., 2021; Summers et al., 2012) and was distinct from the other forms discussed above in structure and focus. In these programs, PAs delivered brief interventions consisting of one to four two-hour sessions to orient parents to the service and provide information about their specific situation, coping tools, and a platform for presenting questions and expressing their needs. Theoretical Frameworks In our analysis of the 24 programs, we identified three main theoretical frameworks that serve as their foundations, with multiple theories often represented in each program. The most prevalent frameworks were found in 15 programs and consisted of the “empowerment theory and strength-based approaches”. These humanistic approaches emphasize individuals’ capacity to take control of their lives, develop agency, and enhance their sense of efficacy. Consequently, these programs focused on creating opportunities for parents, strengthening their abilities, and supporting them in expressing their needs and concerns. In contrast to the somewhat individual-focused framework mentioned above, the second group of theoretical frameworks was grounded in “mutual aid ideas and social network theories” and included nine programs. These frameworks emphasized the relational aspects of parents’ lives, highlighting the importance of formal and informal support networks. These programs invested in helping parents expand relationships with other parents involved with CPS and other communities. Additionally, they aimed to enhance parents’ formal support networks by connecting them with relevant community resources and services and facilitating the development of beneficial relationships with established entities. The last group of theoretical frameworks fell under “critical theories”, which centered on the social structures that generated and perpetuated social inequality within CPS. The few programs informed by these frameworks (n = 5) prioritized system-level advocacy and operated based on the belief that parent advocacy was an effective intervention to support families and a transformative practice capable of reshaping the CPS. That is, this theoretical framework perceived the CPS as a structurally racist system that predominantly harmed Black, Asian, and minority ethnic communities and families living in poverty (Castellano, 2020). Impacts of Parent Peer Advocacy and Support Programs The key findings of the 45 studies that examined 24 parent peer advocacy and support programs addressed the perceived value or effectiveness of program components and impact. Impact-related findings typically focused on case-related outcomes, but some studies investigated experiential outcomes, such as impacts on individual (parent, mentor) behavior, understanding, well-being, and family functioning. A limited number of studies addressed impact at an organizational or system level. Impact-related findings were primarily associated with child welfare and protection program settings (n = 13) due to their prevalence in the sample. Studies of programs in multidisciplinary legal representation settings did not typically address parent advocacy-related impact; instead, they specifically focused on wider program impact. However, some studies acknowledged the value (Haight et al., 2015) or take-up (University of Michigan Law School [UMLS, 2013]) of parent advocate support. Other types of parent peer advocacy settings, CP and parental cognitive disability programs, did not examine overall outcomes but highlighted the lack of support available to these parents in coping with challenges. Experiential Outcomes Across studies and program settings, experiential outcomes broadly addressed changes in parents’ attitudes towards, understanding of, and engagement with services and changes in perceived well-being. In parent advocacy programs in child welfare and protection settings, parents experienced an improved understanding of the reasons for CPS involvement and safety concerns, felt ‘better off,’ and experienced positive behavioral changes and improved engagement in CPS processes (Lalayants, 2012a, 2014, 2019; Lalayants et al., 2019). Positive impact was also identified with perceptions of personal growth and enhanced support (emotional and concrete) for parents (Frame et al., 2006; Lalayants et al., 2015; Soffer-Elnekave et al., 2020). More limited evidence suggests that the positive impact extends to child well-being and family functioning over time in some cases (Ainsworth, 2019; Polinsky et al., 2010), though further investigation is needed. Similar findings extend to parent peer advocacy and support programs in other CP-related settings. CP and substance misuse settings identified parent attitudinal changes aligned with CP goals (Rockhill et al., 2015) and high levels of treatment participation, satisfaction, and enhanced support (Green et al., 2015, 2016). Findings suggest parent peer advocacy and support also positively affect parent well-being, leading to positive self-perception and feelings of empowerment (Green et al., 2015; Rockhill et al., 2015). In CP and mental health program settings, parents experienced increased engagement with mental health treatment and reduced levels of depression, though no associated changes in perceived mental health stigma were found (Acri, Hamovitch, et al., 2021). Family and dependency court program settings reflect high levels of service satisfaction, with the mentor role promoting engagement (Drabble et al., 2016) and an improved understanding of and attitude toward the process and engagement (Summers et al., 2012). Studies also indicate that PAs were more likely than other parents to comply with court attendance, case plans, and visitation (Bohannan et al., 2016; Summers et al., 2012; Trescher, 2020). Experiential outcome findings in studies of multidisciplinary legal representation programs, while not specific to the parent advocacy components, were consistent with findings from other settings and included parents feeling heard, improved contact, and high levels of service satisfaction (Haight et al., 2015; UMLS, 2013). Among regional initiatives, the Parent Mutual Aid Organization identified improved social support with less reliance on CPS professionals and improved parent well-being (improved self-esteem and daily coping skills) and competence (Cameron, 2002; Cameron & Birnie-Lefcovitch, 2000). Experiential outcomes for parent advocates were also identified in two kinds of parent peer advocacy and support settings: child welfare and protection programs and CP and substance misuse programs. Findings reveal benefits for mentors, including personal fulfillment (Lalayants 2012a, 2012b), personal and collective empowerment (Damman, 2018; Leake et al., 2012), and peer support (Berrick, Cohen, et al., 2011; Leake et al., 2012). Huebner et al. (2018) found that new opportunities and successful employment were among the reasons for high turnover, though some mentors did exit due to challenges. A more recent study by Lalayants (2021) also suggested the potential for negative impact, with some advocates reporting secondary traumatic stress. Case Outcomes Case outcomes across studies focused on referral screening, investigation rates (initial referral, maltreatment reoccurrence), out-of-home care (initial and subsequent out-of-home placement, kinship placement), and permanency (reunification, time in out-of-home care, time to permanency, type of permanency, termination of parental rights). Out-of-home care and permanency were the most consistent outcome domains for child welfare and protection program findings. Two New York-based programs identified family preservation and child safety as a qualitative theme (Lalayants, 2013) and observed a decrease in out-of-home placements, with more children remaining at home or in kinship arrangements (Lalayants et al., 2021). Similar findings were reported in the Iowa Parent Partner program, which showed a decreased likelihood of out-of-home placement initially (Midwest Child Welfare Implementation Center [MCWIC, 2014]) and 12 months post-reunification (Chambers, 2019). Four studies that examined reunification rates identified an increased likelihood of returning home (Berrick, Young, et al., 2011; Chambers, 2019; MCWIC, 2014) across three programs, with one study (Enano et al., 2017) identifying African American mothers as being more likely to be reunited with their children. Other case outcomes for parent peer advocacy and support in child welfare and protection program settings were less consistent or less well defined. Some qualitative findings reported improved case outcomes more broadly (Frame et al., 2006; Soffer-Elnekave et al., 2020). A study of Parents Anonymous peer support groups for parents at risk or already involved with CPS identified a decreased likelihood of initial referral for parents not yet referred to CPS (Burnson et al., 2021). Studies of CPS-involved families that examined referral, screening, or investigation rates found no difference in maltreatment recurrence (Lalayants et al., 2019, 2021). Findings related to case outcomes were limited in other parent advocacy settings, primarily due to the relatively small number of studies identified. Two studies examined permanency-related outcomes associated with the Parent for Parent (P4P) program based in a dependency court setting. The program was associated with lower rates of termination of parental rights and higher rates of reunification (Bohannan et al., 2016; Trescher, 2020). Studies of programs in CP and substance misuse settings identified fewer positive outcomes in at least one of the two programs. Green et al. (2015, 2016) found no significant difference in outcomes related to referral screening, investigation (maltreatment reoccurrence after one year), out-of-home care (foster care re-entry after one year), or permanency (time in foster care; time to permanency; permanency type). A more recent study of Kentucky’s Peer Recovery Support Service (START) identified face-to-face visits as a factor in increasing the odds of reunification and service refusal or non-attendance as a factor in decreasing the likelihood of reunification (Huebner et al., 2018). Organizational and System-Level Outcomes Evidence of service and wider system-level impact was observed in three types of settings, primarily child welfare and protection program settings, but also in a CP and substance misuse program and a regional system-level initiative setting. Four studies that examined organizational and system-level impact in child welfare and protection program settings revealed several potential benefits, including a more family-centered approach (Damman, 2018; Lalayants, 2012b, 2013), positive peer-worker relationships (Lalayants, 2012b), and shifts in agency culture (Leake et al., 2012) that included more humane, fair, participatory and effective examples of practice (Damman, 2018). Furthermore, a Canadian Regional Initiative setting program that offered informal parent support groups noted cost savings associated with group work approaches as an additional outcome (Cameron, 2002). This scoping review examined empirical literature on parent peer advocacy, mentoring, and support programs to develop a systematic mapping of existing models, program structures, and direct practices. By reviewing 25 years of research, the study explored the theoretical frameworks underpinning the design and delivery of these programs as well as program benefits and outcomes. Several key findings and their implications are discussed below. First, the significant variation in parent peer advocacy and support programs’ settings, target populations, aims, parent advocate roles, and underlying theoretical frameworks points to the importance of contextualizing practice and research while considering within-group differences in program type and characteristics. Accordingly, the findings of this review provide a first-of-its-kind mapping of CP programs in which parents with lived CP experience participate in service delivery as peer mentors and advocates. By outlining seven settings in which such programs operate, six categories of expected outcomes, four kinds of roles undertaken by PAs, and three theoretical frameworks that underlie practice (see Figure 2), the findings provide a comprehensive understanding of the field of practice and associated outcomes. This understanding can provide researchers, policymakers, and practitioners a springboard to designing programs that fit their unique contexts and goals. The studies examined in this review provide evidence of positive outcomes associated with PA programs. These outcomes include increased parent engagement with services, a decrease in out-of-home care placements for children, higher rates of children remaining with their families, a focus on placing children with relatives, improved rates of reunification, and a reduced likelihood of re-entry into the child welfare system when out-of-home placement is necessary. While these findings are important, further research is needed to continue examining the various models. Specifically, review findings indicated substantial variation in the evidence base across different program settings. Most documented evidence focused on child welfare and protection settings, while there was a more limited or inconclusive evidence base in other settings. The positive experiential outcomes associated with PA programs comprise another significant finding of this scoping review. Numerous studies provided evidence of the value of the immediate feeling of support experienced by parents who shared similar lived experiences with PAs. This sense of support was linked to feeling understood, accepted, and empowered and consequently shaped the overall experience of parents involved in the system. While previous reviews focused on case outcomes, this review emphasizes the importance of focusing on experiential outcomes in future practice and research. Importantly, such outcomes have the potential to improve overall family outcomes significantly, but they also stand out independently as crucial for developing rights-based anti-oppressive practice in CP. Parents are entitled to receive respectful, non-shaming, and just CP services regardless of their ability to adhere to system requirements or case plans. Thus, we wish to emphasize that some parent peer advocacy and support program types may be beneficial and align with recent calls to re-vision and reimagine CP based on ethical considerations (Gray et al., 2016). Accordingly, the findings imply a need to develop equality- and rights-based measures in establishing program value and effectiveness (see McPherson & Abell, 2020). Furthermore, future studies should examine links and patterns by type of intervention (peer advocacy, family support, and mentoring programs) in terms of theoretical frameworks or reported outcomes. Additionally, exploring how PAs can promote equity in relation to race and disability within the context of child welfare is crucial. As the findings show, only a minority of the programs operated within a critical framework that highlighted the importance of addressing oppression and injustice based on race or disability. Hence, understanding the specific strategies and approaches PAs use to address disparities, advocate for equitable services, and support families from diverse backgrounds or contexts can contribute to creating a more equitable and inclusive child welfare system. Similarly, in the context of calls for system reform, the review identified only a limited number of studies that described the macro-level involvement of PAs. Although PA programs are generally recognized for promoting empowerment, equity, and the inclusion of parents’ voices to effect transformative changes to CP systems, and PAs participate in various agency meetings where program and policy decisions are made, very little is known about their involvement and impact on organizational and policy/system levels. There is a pressing need to document and establish empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness and impact of these efforts. It is crucial to study the involvement of PAs at the macro level, specifically examining their experiences and the types of activities in which they engage. Doing so will shed light on how PAs represent parents’ voices at this level and investigate how their involvement contributes to and influences service improvement, programming, culture change, and child welfare reforms. Such evidence would help identify the benefits and impact of PAs’ contributions at the organizational and system levels, identify potential barriers to their inclusion and involvement, reveal opportunities for more robust engagement, and recognize the role of PAs in significant organizational and system-level decision-making processes. The studies analyzed in this scoping review indicate that parent advocacy, recognizing the variations in type and characteristics, holds promise as a model for improving outcomes for families and children in child welfare. However, it is important to consider several of this study’s limitations when interpreting its findings. For instance, the inclusion criteria were limited to studies published in English, which may have restricted the number of identified programs and the depth of description. Expanding the language criteria or employing additional strategies to capture non-English publications could diversify the representation of countries in future research. Future studies seeking a more nuanced exploration of regional or contextual variations could also delve into cross-country comparisons. While conducting this scoping review, we aimed to identify the entities initiating, supporting, or funding PA programs, including paid/volunteer roles and supervision. However, our thorough review revealed limited and inconsistent information about these program aspects in the publications, making it impossible to include this information. Future research should investigate the initiation and support of PA programs, for example, whether they stem from the CP system or parents themselves, and explore program funding. Such an exploration could elucidate implications for service delivery, accessibility, and impact on power structures within these systems. It is important to note that this review identified a disproportionate representation of US-based research in this area. Unraveling the precise reasons behind this overrepresentation requires a comprehensive examination of multiple factors—variations in family support policies, funding priorities, emphasis on giving parents a voice in these processes, and others. Addressing these factors demands an in-depth exploration of country-specific policies and a thorough policy analysis. Future research endeavors should investigate these aspects to reveal the nuanced dynamics that contribute to the prominence of certain regions in the discourse on family engagement in child welfare. Finally, due to the considerable heterogeneity in operational definitions and samples, we employed broad inclusion criteria that led to a diverse selection of studies with different research standards. Although we considered each study’s limitations, we did not systematically assess the quality of the studies because our research questions aimed to map models, practices, and findings. Despite these limitations, this scoping review provides the most comprehensive overview of the existing literature on parent peer advocacy and support in CP and has the potential to inform future practice and research. Conclusion By executing a comprehensive search of empirical peer-reviewed and grey literature sources spanning 25 years, this study mapped CPS-related parent peer advocacy and support program theories, rationales, program types, structures, practices, and impacts systematically and in detail. Early evaluations have demonstrated positive case and experiential impacts, and particular models of parent peer advocacy promise to promote positive family and child welfare outcomes. Nonetheless, there are gaps in the literature that need to be addressed. To further inform the field, future research should continue to collect and analyze evidence on the impact of parent peer advocacy and support on individual (child, parent, advocate), family, and system (organizational, system, including economic) outcomes (immediate to long term) as well as parent peer advocacy and support model development and implementation with attention to associated case outcomes, PA workforce development, and sustainability. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Saar-Heiman, Y., Damma, J., Lalayants, M., & Gupta, A. (2024). Parent peer advocacy, mentoring, and support in child protection: A scoping review of programs and services. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 73-88. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a5 |

Cite this article as: Saar-Heiman, Y., Damman, J. L., Lalayants, M., and Gupta, A. (2024). Parent Peer Advocacy, Mentoring, and Support in Child Protection: A Scoping Review of Programs and Services. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 73 - 88. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a5

Correspondence: heiman@bgu.ac.il (Y. Saar-Heiman).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef